Introduction

In today’s interconnected world, online news platforms have become primary sources of information, shaping public perception on critical issues. Nigerian Newspapers Online are no exception, serving as vital conduits of news and information for both domestic and international audiences. The way these online media outlets report on sensitive topics like suicide is of paramount importance. Media coverage significantly influences public understanding and can have profound effects, especially on vulnerable populations. Research has consistently shown that media reporting on suicide can, unfortunately, contribute to ‘copycat’ behaviors if not handled responsibly. This is particularly concerning given the increasing accessibility of news through online platforms.

Studies evaluating media adherence to suicide reporting guidelines have grown globally, yet research focusing specifically on Nigeria remains limited. This article delves into the practices of Nigerian newspapers online, examining their coverage of suicide in 2021. It is based on a content analysis study that assessed the prevalence of harmful and helpful reporting cues as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. Understanding the current landscape of suicide reporting in Nigerian online news is crucial for advocating for responsible journalism and improved public health outcomes.

Harmful Reporting Cues in Nigerian Online Newspapers

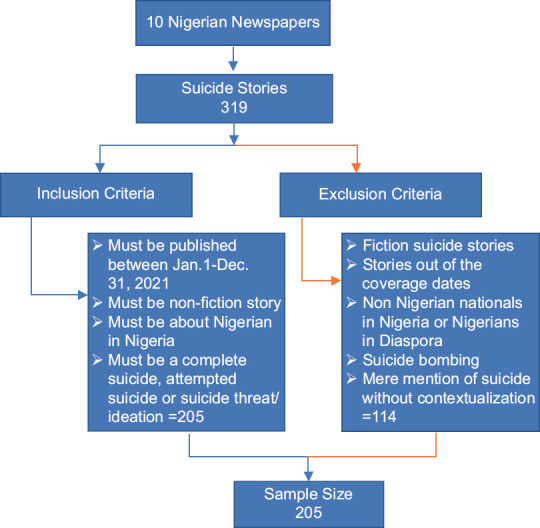

A quantitative content analysis was conducted on 205 online suicide-related news stories from ten prominent Nigerian newspapers. These newspapers, selected for their wide reach and significant online presence, were analyzed to determine the extent to which they employed potentially harmful reporting practices. The findings revealed a disturbing trend: harmful reporting cues were highly prevalent, overshadowing any helpful reporting elements.

One of the most concerning findings was the sensationalization of suicide in headlines. A staggering 95.6% of the analyzed stories mentioned “suicide” directly in the headline. This prominent placement can contribute to the normalization and over-exposure of suicide, potentially increasing its contagion effect. Furthermore, 79.5% of the stories provided explicit details about the methods used in suicides. Describing suicide methods in detail is considered harmful as it can provide vulnerable individuals with blueprints for imitation.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 1: Flowchart illustrating the process of selecting suicide-related news stories from Nigerian online newspapers for content analysis.

The study also found that 66.3% of the stories presented a simplistic, mono-causal explanation for suicide. Attributing suicide to a single factor oversimplifies a complex issue often rooted in multiple interacting causes, including mental health conditions. Visual elements also contributed to harmful reporting, with 59% of stories featuring images of suicide victims or suicide-related graphics. Such images can be distressing and sensationalize the act of suicide.

Further analysis revealed that victim identification was a common practice. Nigerian newspapers online frequently disclosed personal details of suicide victims, with 94.1% mentioning the victim’s name, 74.6% their occupation, and 66.3% their age. This level of detail, while perhaps intended to provide context, can contribute to increased distress for bereaved families and communities, and potentially glorify the deceased.

Lack of Helpful Reporting Cues

In stark contrast to the prevalence of harmful reporting, helpful suicide reporting cues were almost entirely absent in Nigerian newspapers online during the study period. These helpful cues, recommended by the WHO and international guidelines, are crucial for suicide prevention and responsible media practice.

Alarmingly, less than 4% of the stories included any information that could be considered helpful. Only a tiny fraction (3.9%) mentioned warning signs of suicide, which are vital for public education and early intervention. Similarly, reporting on mental health expertise and professional opinions was negligible (1.5%), missing an opportunity to provide valuable context and destigmatize mental health issues related to suicide.

Table 1: Table showing the distribution of suicide-related news stories included in the study, categorized by Nigerian newspaper.

The study also found a near-total absence of information on suicide prevention programs or support services. Providing contact details and resources for help-seeking is a cornerstone of responsible suicide reporting, yet only 1.5% of stories offered such information. Furthermore, research findings and population-level statistics on suicide, which could provide a broader and more informed perspective, were reported in a mere 1% of the stories.

While a slightly higher percentage (22.9%) of stories linked suicide to mental illness, and 13.2% mentioned the impact on the bereaved, these figures remain low compared to the overwhelming presence of harmful reporting cues. The overall picture is one of missed opportunities to educate the public, dispel myths, and promote help-seeking behaviors in suicide reporting by Nigerian newspapers online.

Discussion: Implications of Harmful Reporting

The consistent prevalence of harmful suicide reporting practices in Nigerian newspapers online has serious implications for suicide prevention efforts in the country. Irresponsible media coverage can contribute to the ‘Werther effect,’ where vulnerable individuals are more likely to imitate reported suicides, particularly when reporting is sensationalized or provides detailed methods. Conversely, responsible reporting, known as the ‘Papageno effect,’ can encourage help-seeking and promote positive coping mechanisms. The current study suggests that Nigerian online media are, unintentionally, leaning towards the harmful ‘Werther effect.’

These findings align with previous research in other low and middle-income countries and echo concerns raised in earlier studies within Africa, including Ghana and Nigeria itself. However, they contrast somewhat with findings from Egypt, where some adherence to WHO guidelines was observed. This highlights that while the challenge is widespread, there are examples within the African continent suggesting that improvements are possible.

The lack of adherence to WHO guidelines in Nigerian online newspapers could be attributed to several factors. These may include a lack of awareness among journalists and editors regarding responsible suicide reporting, insufficient training, and the pressures of a competitive news environment that may prioritize sensationalism over responsible journalism. Cultural sensitivities and the stigma surrounding mental health in Nigeria might also play a role in shaping reporting practices.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study provides a critical snapshot of suicide reporting in Nigerian newspapers online, revealing a concerning dominance of harmful practices and a significant absence of helpful, preventative messaging. The findings underscore the urgent need for intervention to improve media practices and align them with international guidelines.

To mitigate the risks associated with harmful suicide reporting, and to harness the potential of online media for suicide prevention, several recommendations are crucial:

-

Awareness and Training: There is a pressing need to raise awareness and provide training for health and crime reporters, as well as editors, in Nigerian news organizations regarding WHO suicide reporting guidelines. This training should emphasize the potential harm of sensationalized reporting and the importance of incorporating helpful cues.

-

Development of Localized Guidelines: Stakeholders, including mental health experts, media practitioners, researchers, and policymakers, should collaborate to develop Nigeria-specific guidelines for suicide reporting. These guidelines should be tailored to the Nigerian socio-cultural context and legal framework, while remaining consistent with international best practices.

-

Promoting Responsible Journalism: Media organizations should be encouraged to adopt and implement these guidelines, prioritizing responsible journalism over sensationalism in suicide coverage. This may involve establishing internal editorial policies and promoting a culture of ethical reporting.

-

Further Research: Future research should expand beyond online newspapers to include offline media and other platforms, such as broadcast and social media, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of suicide reporting across the Nigerian media landscape. Investigating the actual impact of harmful reporting on vulnerable populations in Nigeria is also a critical area for future study.

By addressing these issues, it is possible to transform Nigerian newspapers online from potential contributors to the problem of suicide contagion into powerful allies in suicide prevention. Responsible media coverage is not just an ethical imperative; it is a vital public health strategy.

References

[1] Armstrong G, Vijayakumar L, Radhakrishnan R, et al. (2018). Adherence to WHO guidelines for media reporting of suicide in selected English newspapers in India. Asian J Psychiatr; 37:91–5.

[2] Sisask M, Värnik A. (2012). Media roles in suicide prevention: a systematic review. World Psychiatry; 11:153–61.

[3] Phillips DP. (1974). The influence of suggestion on suicide: substantive and theoretical implications of the Werther effect. Am Sociol Rev; 39:340–54.

[4] Niederkrotenthaler T, Till B, кристине Herberth A, et al. (2010). Impact of media reporting on suicide: a population-based ecological study. Soc Sci Med; 71:1911–6.

[5] Stack S. (2003). Media coverage as a risk factor in suicide. J Epidemiol Community Health; 57:238–40.

[6] Michel K, Valach L. (2011). Suicide and the media. In: Wasserman D, editor. Oxford textbook of suicidology. Oxford: Oxford University Press; pp. 575–85.

[7] Hawton K, Williams KE. (2002). Influences of the media on suicide. BMJ; 325:1379–82.

[8] World Health Organization. (2017). Preventing suicide: a resource for media professionals. Geneva: WHO;

[9] Beautrais AL. (2007). Media guidelines for reporting suicide. Crisis; 28(Suppl 1):53–62.

[10] Mental Health Media Charter. (2010). Mental health media charter. London: Mental Health Media Charter;

[11] Quarshie EN, Okoro SE, Arhinful DK. (2020). Media reporting of suicide in Ghana: adherence to the WHO guidelines. BMC Public Health; 20:1–8.

[12] Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. (2016). Media guidelines for responsible reporting of suicide and mental illness. Melbourne: RANZCP;

[13] Samaritans. (2013). Media guidelines for reporting suicide. London: Samaritans;

[14] Beyond Blue. (2014). Media guidelines for reporting suicide. Melbourne: Beyond Blue;

[15] Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention. (2017). Media guidelines for reporting suicide. Ottawa, ON: CASP;

[16] Jachi R, Vijayakumar L, Rajkumar AP, et al. (2014). Media reporting of suicides: are they following the guidelines? Indian J Psychiatry; 56:379–84.

[17] Khan M, Yousafzai AW, Rasool G, et al. (2017). Media reporting of suicide in Pakistan: content analysis of Urdu newspapers. BMC Public Health; 17:1–8.

[18] Chen Y, Li Z, Qin P, et al. (2012). Media reporting of suicide in China: a content analysis of newspaper reports. Crisis; 33:146–52.

[19] Yip PS, Fu KW, Chan A, et al. (2006). Media watch on suicide: recommendations for media reporting of suicides in Hong Kong. Crisis; 27:141–7.

[20] Chan LF, Yip PS. (2015). Media influence on suicidal behavior: a review of the evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health; 12:12897–930.

[21] Ernawati J, Ariati EN, Musthofa SB. (2019). Media reporting of suicide in Indonesia: a content analysis of online news reports. Jurnal Psikologi Sosial; 17:1–10.

[22] Rahman MS, Khan MM, Karim ME. (2018). Media reporting of suicide in Bangladesh: a content analysis of national newspapers. BMC Public Health; 18:1–9.

[23] Mesbah M. (2015). Media coverage of suicide in Egypt: adherence to WHO guidelines. Omega (Westport); 72:57–71.

[24] Oyetunji TO, Aremu AO, Olagunju AT, et al. (2021). A 10-year review of media reports of suicide in Nigeria: trend and adherence to the World Health Organization guidelines. Int J Ment Health Syst; 15:1–10.

[25] WHO. (2019). Suicide in the world: global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization;

[26] Oshodi YO, Abdulmalik JO, Ola BA, et al. (2010). Suicide in Nigeria: sociodemographic study. Niger J Clin Pract; 13:381–5.

[27] Krippendorff K. (2018). Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications;