Becoming a Liverpool supporter in September 1991, as I turned six, marked the beginning of a long wait – three decades, to be exact – for a league title. Few fans had endured such a lengthy drought before witnessing their team lift that coveted trophy. “Just once,” I’d often tell myself, “if I could see us win it just once, I’d be content in football forever.”

Of course, that sentiment proved fleeting. Match days still bring a rush of nerves, a glorious anxiety that’s essential. Without it, the exhilaration of a Liverpool victory wouldn’t be the same. The downside, naturally, is the low that follows when the team underperforms. “Why do I put myself through this?” I ponder on those darker days. “Why can’t I simply enjoy music, films, things in life not dictated by an outcome I can’t influence?” But this very emotional rollercoaster is the essence of why humanity is drawn to sport. Nothing else quite replicates that unique buzz.

These are undeniably golden times to be a Liverpool fan. We boast arguably the most talented squad I’ve ever witnessed, guided by a manager of unparalleled genius and charisma. If given the chance, I might even choose to spend Christmas with Jürgen Klopp over my own family! For two glorious years, victories were almost routine. It has been, in a word, incredible.

Yet, venturing into certain corners of social media, one might get a vastly different impression. Here, you encounter a peculiar breed of intensely Online Fans. This isn’t a blanket statement about all Liverpool supporters online, but rather a focus on a specific group engaging with the club in ways that many would find peculiar. While numerically small – perhaps around a thousand accounts within a global fanbase of millions – for simplicity, I’ll refer to them as “online fans” or “Twitter fans“.

It’s been apparent for some time that “Liverpool Twitter” exists as a distinct entity, almost a self-contained digital realm within the broader Twitter landscape. My own engagement is limited; when I tweet about the club, it’s primarily to connect with my own followers who happen to be Liverpool fans. However, this past summer, I became captivated by this particular type of online supporter, seemingly evolving in response to the team’s relative setbacks last season, following an era of unprecedented success. Observing them became an irresistible fascination, akin to watching ducks in a pond. Initially, their behavior was perplexing, but it seemed linked to youth culture and the nature of modern capitalism.

These accounts fascinate me because their engagement with football appears utterly disconnected from my own experience as a fan – an experience largely shaped by events on the pitch (a radical concept, I know!). Their vocabulary is foreign to the football conversations in Dublin pubs, at Anfield, or among my Liverpool-supporting friends, whether in person or on WhatsApp. This phenomenon isn’t exclusive to Liverpool; every club seems to harbor a similar online contingent. I focus on Liverpool as my lens into this peculiar online culture because it’s what I know intimately. It wouldn’t surprise me if readers recognize similar patterns within their own club’s fan communities.

This isn’t an organized movement with a clear leader, making precise categorization difficult. From my observations, they are predominantly young – teenagers or in their early twenties, though some are older and arguably should know better. And they are vocal. Extremely vocal. They frequently overwhelm the mentions of journalists, news outlets, and the club’s official accounts. Beyond their demographics, these online fans generally share three core traits:

One: Transfers are paramount. For these fans, player acquisitions are the ultimate yardstick of a club’s ambition and success. Liverpool had a relatively subdued summer transfer window, though they did address a crucial area by signing center-back Ibrahima Konate. However, this was insufficient for fans who prioritize “winning” the transfer window as the definitive measure of a club’s health. Liverpool Twitter, in the window’s final days, descended into near chaos.

Liverpool’s impressive end-of-season run to secure Champions League qualification, including Alisson’s dramatic late winner against West Brom, seemed almost irrelevant. I repeatedly encountered sentiments like, “What was the point of Champions League qualification if we’re not signing anyone?” It’s as if those victories, those iconic moments, held no intrinsic value, and the sole purpose of Champions League participation was to generate funds for “bigger, better, and more expensive” transfers. Incredibly, they even managed to link the recent military coup in Guinea to transfer activity.

Frustration over perceived lack of transfer activity

Frustration over perceived lack of transfer activity

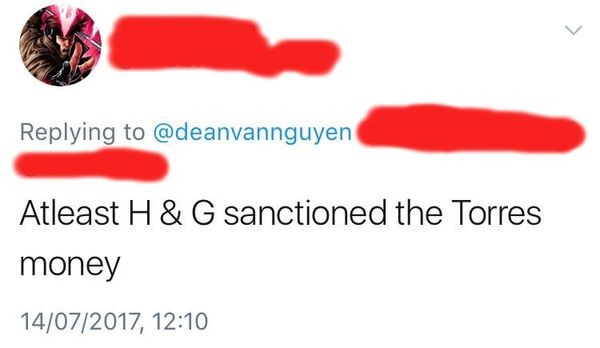

Insufficient transfer activity leads to calls for ownership change, demanding custodians who will invest heavily in players, as transfers are the only metric by which owners should be judged. A few years prior, someone attempted to argue that Liverpool’s previous owners, Tom Hicks and George Gillett – figures who nearly bankrupted the club – were superior to the current Fenway Sports Group (FSG) because “at least” Hicks and Gillett oversaw the signing of Fernando Torres. Similarly, these online fans look enviously at Manchester United, impressed by their three summer signings, despite the Glazer family, United’s owners, demonstrably draining wealth from the club, while FSG have never extracted funds from Liverpool. FSG’s return on investment comes from the club’s increased valuation. Only someone fixated on transfers above all else could reach such a conclusion.

Hicks and Gillett era contrasted with Torres signing

Hicks and Gillett era contrasted with Torres signing

Transfers are undeniably crucial in football. Liverpool’s current strength is partly due to excellent recruitment during the Klopp era (though coaching, tactics, training, and youth development are equally vital). Personally, I would have welcomed another attacking addition recently. However, I’m mature enough to recognize that real-world recruitment is more complex than in Football Manager, and a season’s success isn’t solely determined by transfer activity. Most football fans believe their squad could benefit from a few more players. My mild disappointment at not signing a forward is overshadowed by the reality that this is the strongest Liverpool squad I have ever witnessed.

This transfer obsession has transcended squad improvement; it’s become a separate hobby, tangentially related to the sport itself. This mindset requires believing that Liverpool’s existing 26 first-team players are incapable of success this season, but adding player number 27 would magically solve everything. It necessitates assuming every transfer is a guaranteed positive, ignoring the reality that poor signings often weaken a squad. It demands believing that every setback this season could have been avoided with more signings in previous windows.

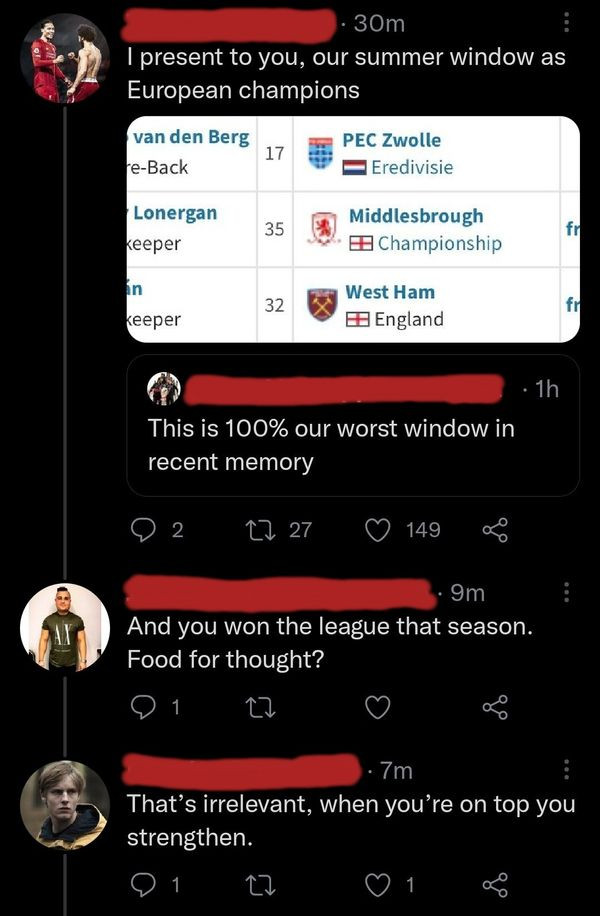

Online fans frequently point to the quiet summer of 2019 as the origin of perceived problems. Yet, that summer directly preceded Liverpool winning both the Champions League and the Premier League title. At the time, Nicolas Pépé, a sought-after Ivorian player, was heavily linked with Liverpool, becoming a fixation for transfer-obsessed fans. He joined Arsenal that summer and struggled in his first season. Would Liverpool have won the league with Pépé? Uncertain. But rewriting history from the summer before a 30-year title win seems illogical.

Premier League title win deemed "irrelevant" without transfer window win

Premier League title win deemed "irrelevant" without transfer window win

To be fair, the prominence of transfers in football culture is a broader issue than just this Liverpool fan subset. There’s some sympathy to be had for those drawn into this obsession. Football media is saturated with transfer news. The immense financial stakes ensure many are invested in making transfers a cornerstone of the game. Every football news site emphasizes sensational rumors; Sky Sports News has built its brand around transfers. As Rory Smith astutely wrote in 2015, “The cult of the transfer has tricked us all into thinking that only signing new players can solve problems. It is has led us to believe in magic bullets.”

Human nature plays a significant role. Many believe a missing piece will complete their lives, and capitalism constantly sells the idea that happiness is purchasable. In this context, it’s easy to be seduced by the idea that one more player will fix everything. But football, like life, rarely follows such neat narratives.

Two: If online fans cherish transfers, they arguably love online conflict with fellow Liverpool fans even more. Their prevailing attitude is that any fan not fully aligned with their views is an opponent. Much of this resembles classic trolling behavior.

These fans have coined a derogatory term for Liverpool supporters they dislike: “Top Reds.” From what I gather, a Top Red is someone perceived to believe the club is infallible. “Top Reds” are akin to “cancel culture” – largely existing in the minds of those who complain about them. No Liverpool fan believes everything is perfect, just as no fan of any club does.

These rants about Top Reds often include mockery of the Liverpool accent and Scouse dialect. It’s worth emphasizing: Supposed Liverpool fans mock the Liverpool accent and Scouse vernacular. This is a regular occurrence, likely stemming from a perceived disconnect between match-going fans in Liverpool and their more online counterparts, leading to “Top Reds” and “local fans” becoming synonymous in their lexicon. Imagine viewing local fans, the very heart and soul of the club, as a burden. It mirrors the peculiar Irish American who insists those born in Ireland don’t understand Irishness because they don’t engage in the same stereotypical portrayals.

Love it when Liverpool fans take the piss out of the Liverpool accent

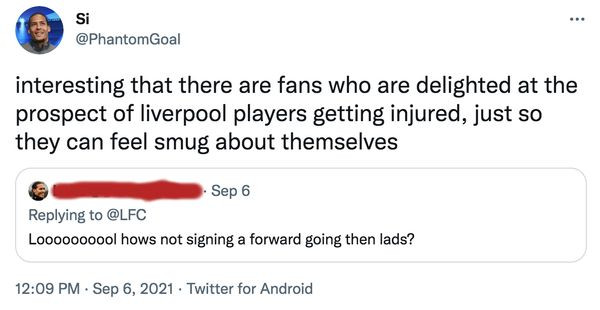

Three: Pessimism reigns supreme. For these online fans, Liverpool is perpetually destined for failure. The paramount concern becomes validating this premonition. Poor results are almost welcomed as proof that the transfer window was a disaster and the owners are ruining the club. Player injuries become occasions for celebration. Any player with a couple of injuries is labeled “injury-prone” and deemed expendable. Current player criticism is rampant, with Divock Origi, a cult hero among many Liverpool fans, frequently targeted.

Screenshot of online fan negativity

Screenshot of online fan negativity

There’s an odd fixation on a match against Atletico Madrid in March 2020, Liverpool’s first significant defeat in roughly 14 months – a period of remarkable success. That online fans constantly revisit this single setback within a historically great period highlights an inability to grasp that in sports, and in life, things don’t always go your way.

A pervasive sense of entitlement underlies this: the notion that fans inherently deserve new players and constant success. The implication being that fans of clubs Liverpool outspend and defeat are somehow less deserving.

Again, a critique of capitalism is relevant. A mindset prevails that a football club exists solely to win and be consumed. Players are commodities, valued only for their utility to the machine. Once a player’s usefulness diminishes, due to form or injury, they become less valuable than the fleeting dopamine rush of a new transfer. Karl Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism – relationships between people perceived as relationships between things – helps explain this perspective.

This reminds me of Gamergate. Football, like video games, is mainstream culture, yet harbors pockets of intense anger, often among young men. Conspiracy theories flourish – journalists who disagree are accused of being paid by the club; data showing Liverpool’s high payroll is dismissed as fabricated. Vile misogyny is also present, directed at Linda Pizzuti Henry, FSG shareholder and wife of principal owner John W. Henry. Anonymity is the norm.

It’s a deeply fatalistic way to experience football. Being invested enough in Liverpool to dedicate a social media presence to the club, yet unable to find any joy in it. A bleak existence. If social media is an artificial world, their fandom feels equally artificial, detached from the club’s essence. It’s sterile and devoid of the club’s most appealing aspects – history, tradition, the city itself. Winning the league was an intensely emotional experience. Looking at LFC Twitter, that emotion is often absent. These online fans may present as supporters, but it’s a pale imitation.

Returning to the contentious topic of ownership, I anticipate accusations of being an “FSG apologist”—a nonsensical label—and this article being dismissed as an attempt to undermine their “FSG Out” movement. Unlike most advocating for ownership change, I have a vision for a Liverpool without FSG: fan ownership. I’ve never desired the club to be subject to the whims of a billionaire.

However, I align with many Liverpool fans: I have no particular affection for FSG, but view them as relatively responsible owners who have overseen club development and on-field success without jeopardizing its future as previous owners did. Simply put, if on the day they acquired the club, I was offered a Champions League and Premier League title within a decade, I’d have accepted instantly.

Their tenure hasn’t been without missteps: forced reversals on staff furloughing, ticket price increases, and the European Super League – though they did backtrack. Communication could improve to maintain fan support; fewer apologies from Henry would be welcome. (Online fans occasionally acknowledge these incidents, but often superficially. Many transparently admitted after the Super League fiasco they’d forgive everything if FSG signed Kylian Mbappe.) Could FSG invest more aggressively, particularly to address Covid-related financial gaps? Perhaps. But these missteps require perspective and proportion.

Younger generations, raised on reality TV, tend to simplify complex issues into binary “In” or “Out” choices – even club ownership. This perspective makes nuanced criticism of FSG impossible without being categorized as either “FSG In” or “FSG Out.” Even the phrasing is strange. “Do you want FSG in or out?” is more logical. Instead, owner support or opposition becomes a core fan identity, leaving no room for nuance. And it ignores the crucial question: If not FSG, then who? Without a viable alternative, a new owner is purely hypothetical. When asking someone with #FSGOUT in their profile about their preferred replacement, the answer is often vague: “someone who will do [everything I want].”

There’s also the adage “better the devil you know.” Ethical billionaires are nonexistent, but I’ll take capitalists over oligarchs or nation-states using sportswashing to conceal atrocities. Personally, I believe success through a self-sustaining model is commendable – a fan-owned Liverpool would operate without profit motives. Because of ultra-wealthy individuals funneling vast sums into rival clubs for dubious reasons, owners are now expected to inject personal fortunes. Finding someone willing to invest heavily in Liverpool with no financial return for non-nefarious purposes is improbable. Many clubs have suffered from truly disastrous ownership. Liverpool fans of a certain age (those remembering 2010) know this firsthand. Local supporters spearheaded perhaps the most successful owner-ousting campaign in modern English football history. No anti-FSG campaign will gain traction without support from groups like fan union Spirit of Shankly, regardless of online fan volume.

These are valid topics for discussion, but Twitter debates are often unproductive. Online fans often lack understanding of club operations and resist learning if it contradicts their worldview. Publicly available accounts showing John Henry isn’t funding yacht purchases with transfer money are ignored. This group often randomly selects European players and blames FSG for not signing them. Once, attempting to explain fan ownership to someone, I received a non sequitur about “Top Reds” giving Adrian a 10-year contract. Reality is often absent from these discussions.

Who said anything about us signing Suarez?

The reality is, I believe if Liverpool were to experience the lows of the recent past again, many of these online fans would migrate to other clubs. Not consistently getting what they want from football seems unbearable for them. But supporting a football club inherently involves both highs and lows. Without the lows, the highs would be meaningless.

This is a free post for all the Reds. If you’d like future, generally non-football related newsletters sent to your inbox, please consider subscribing. It’s free unless you want access to everything—in that case you’ve got to pay. If you want to show financial solidarity with a one-off tip, use PayPal.Me